“Dress for the century, not the moment.”

— Valentina’s advice to Greta Garbo

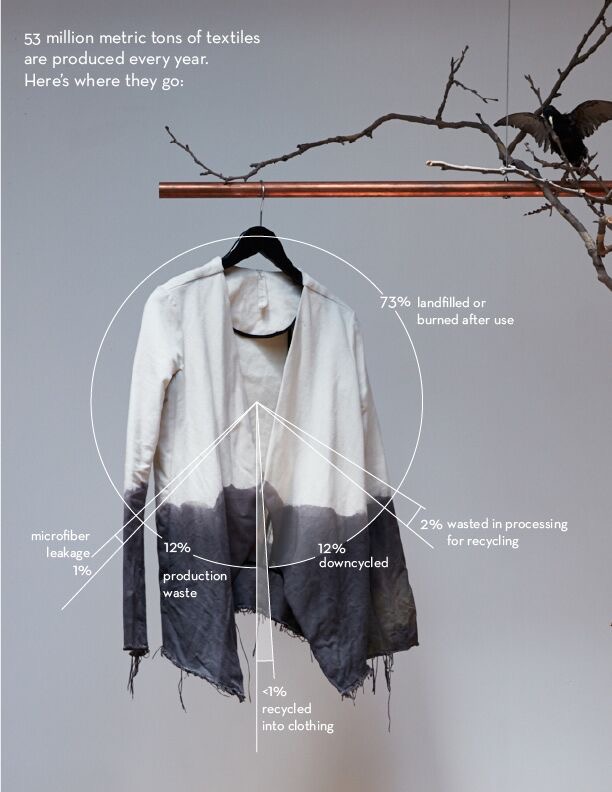

In our era of internet-enabled instant gratification, the cycles of fashion are turning ever faster, and the garment industry is churning out ever more clothes — producing more than 160 times the weight of the Empire State Building in clothing every year, most of which goes to landfills after just a few wearings. Complicated fixes abound, and yet ultimately, what drives all of this mass production is that consumers are buying it. It’s the wearers of clothing, all of us, who have the power to take matters into our own hands, to look to tradition rather than technology and rethink our habits to slow this madness and close the circle.

While we think of textiles as ephemeral, clothing that is well-crafted and lovingly cared for can last for decades, and sometimes longer. As recently as the 1800s, dress styles evolved only every 10 years; as trends changed, women would simply alter their existing gowns accordingly, mending them over the decades as they aged. Yet today, the average garment is worn five times before it’s discarded.

At the Metropolitan Museum’s Costume Institute, head conservator Sarah Scaturro is charged with the preservation of garments ranging from 15th-century menswear to Iris van Herpen’s delicate, futuristic 3D-printed dresses. Her advice on wearing garments as long as possible? It’s not a contest between synthetics and natural fibers, but a matter of how they’re cared for. While synthetics have a reputation for being long-lived, some are in fact chemically volatile and emit toxic gases as they break down, while others shed dangerous microfibers into our water system.

For all types of garments, Scaturro offers this common-sense advice: Avoid extreme conditions (sunlight, heat, damp) and pests; mend as needed, reinforcing stress points; wash less frequently, using just a little soap; and don’t tumble dry.

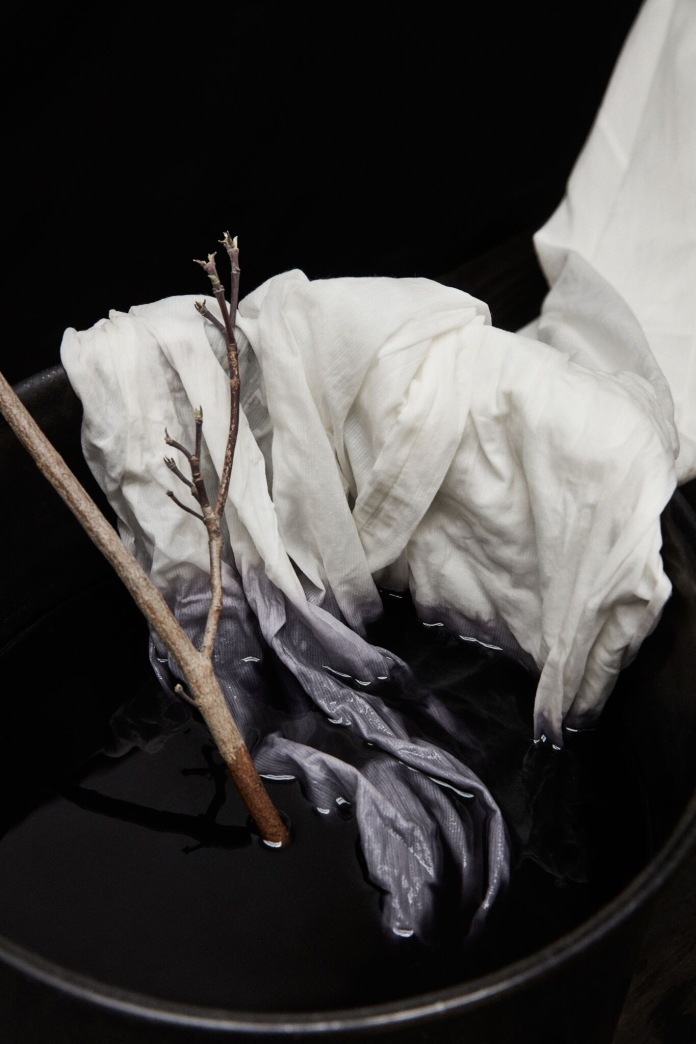

As for mending, there are both modern and time-honored ways to address the holes, tears, or discolorations that can crop up over time. Reweaving, embroidery, and appliqué can be employed either to conceal holes or transform them into decorative elements, as with punk-rock patches or Japanese sashiko stitching. As for stains and fading, in the markets of Morocco, dyers still refresh old garments with new color — a practice recently revived by the Berlin-based, Japan-dyed vintage line Blackyoto, and which can also be done at home.

Parsons School of Design professor Timo Rissanen likes to have a bit of fun with visible mending, both in his creative work and his own wardrobe, and argues for reviving the homemade aesthetic. Having darned his oldest garment, a 25-year-old Norwegian sweater, until it’s acquired an entirely new aesthetic, he finds that lack of preciousness liberating. For those intimidated by the skill required for mending, he suggests a similarly open-minded approach: first learning to stitch buttons and hems, then most crucially, learning to love the results: “The homemade ought to be celebrated. The home-mended ought to be celebrated.”

Once a garment is beyond repair, many forms of recycling beckon. Quilting and piecework — originally ways to layer scrap fabrics into a new textile so strong that it was used for armor in both Japan and Europe — are seeing a revival. Clothing brands including Eileen Fisher, APC, and Nudie Jeans now take back, mend, or resell their lines’ used garments. And yet, as Rissanen points out, what to do with worn-out garments is rarely the issue. “For the most part, garments wearing out is not a problem. It’s much more of a problem that we are not wearing clothes to the point where they actually wear out.”

How, then, as participants in fashion, can we all work more responsibly to avoid filling our planet with our cast-offs? The answer isn’t easy, but it’s surprisingly joyful: To purchase only clothes we truly love and that will have a special place in our wardrobes; and if it’s for a one-time wearing, to rent or buy used. To wear unblended natural fibers, which are healthier for us and our planet. To have a bit of fun with our clothes, embracing making rather than shopping as a social activity.

We don’t have to look far into the past to remember these practices: In Carmen’s Mexican grandmother’s day, women would gather to jointly embroider a large, complex piece as they chatted and socialized. Titania’s mother grew up in the British colonies wearing clothes her own mother handmade for her. And as many people embrace making as a counterpoint to the disembodied computer work that prevails in their day jobs, textile classes have multiplied across the US, from Textile Arts Center in New York to Makers Mess in Los Angeles.

Dressing for the century no longer has to mean, as it did in Garbo’s day, conforming by sticking to the classics. As Sarah Scaturro declares, “It’s possible to assume any style and have it be relevant for both the moment and the century. We are now in the post-post-modern era, which means anything goes, quite literally.”

Timo Rissanen contends that, contrary to today’s assumption that dressing fashionably requires rampant consumerism, “to participate in fashion does not require a great deal, or even any, money” — rather, it demands only “an unbridled imagination and confidence in your ideas.”

It’s time to let our imaginations run free, and dream up a wardrobe, and a world, unencumbered by garment waste.

_____

This article was published by Regeneration magazine September 2018.

Credits:

Article by Titania Inglis and Carmen Artigas

Photos by Shay Platz for Titania Inglis

Infographic by Titania Inglis (based on statistics from Make Fashion Circular, tiny.cc/fibres)